The history of the Seven Stars

At its height the Parish of Redcliffe and surrounds was home to over 200 coaching inns, ale houses and lodgings, some large enough to have had stables for a hundred horses. This bustling community of seafarers, traders and residents was one of the busiest parts of the city.

By the mid 1700’s St Thomas Street and Thomas Lane alone were home to over twenty pubs, inns and taverns. Some even bearing identical names, two pubs called the Bulls Head, and two named the Crown. The Apple Tree, Artichoke, Ball Inn , The Bell, Cow Catch, The Hare, Kings Arms, The Lamb, Nags Head, Pack Horse, Pelican, Plow, Ring of Bells, Sugar Loaf, Three Kings, Three Queens, White Horse, White Lyon,The Worm Tub and of course the Seven Stars.

Neighbours now long gone, casualties of time and the changing face of a growing city.

Today (2020) apart from us at the Seven Stars only six others remain and continue to trade. These are the Portwall Tavern, the Ostrich, the Cornubia (previously known as the Rabbit Warren), the Shakespeare in Victoria Street (formerly Temple Street), the Victoria (now called the Golden Guinea) and the Ship Inn on Redcliffe Hill. The Prince of Wales (now named the Velindra) that re-opened in 2011, has again closed while The Bell in Prewitt Street still stands, but is closed and boarded, and the Kings Head in Victoria Street seems to be a Covid related casualty, and is closed.

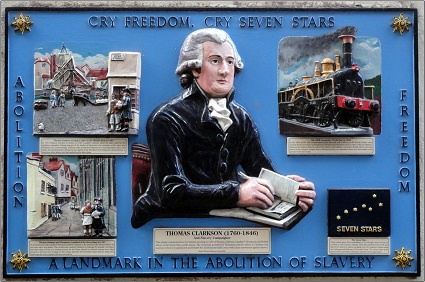

Whilst all pubs have history attached to them the Seven Stars will best be remembered for it’s links to the abolition of slavery. Bristol was a city that had made huge sums from the brokerage of slaves but on May 22nd 1787, the association for the abolition of the slave trade was founded and immediately afterwards Thomas Clarkson, one of the founders, came to Bristol. He was introduced to John Harford, Dr Camplin, Dean Tucker and Matthew Wright and other Quakers. Through them he was introduced to Thompson, landlord of the Seven Stars. He was, Clarkson says, a very intelligent man who was accustomed to receive sailors when discharged at the end of their voyages, to board them and find them berths on other ships. He avoided all connection with the slave trade, declaring that the credit of his house would be ruined if he was known to send those who put themselves under his care, into it.

Whilst all pubs have history attached to them the Seven Stars will best be remembered for it’s links to the abolition of slavery. Bristol was a city that had made huge sums from the brokerage of slaves but on May 22nd 1787, the association for the abolition of the slave trade was founded and immediately afterwards Thomas Clarkson, one of the founders, came to Bristol. He was introduced to John Harford, Dr Camplin, Dean Tucker and Matthew Wright and other Quakers. Through them he was introduced to Thompson, landlord of the Seven Stars. He was, Clarkson says, a very intelligent man who was accustomed to receive sailors when discharged at the end of their voyages, to board them and find them berths on other ships. He avoided all connection with the slave trade, declaring that the credit of his house would be ruined if he was known to send those who put themselves under his care, into it.

With Thompson as a guide, Clarkson, an English gentlemen disguised himself as a miner, with blackened face and wearing working clothes hiding his true identity made nineteen visits to various public houses and inns in the area frequented by masters of slavers to pick up hands. Setting out about twelve midnight, and usually finished between two and three a.m. From his own observations and from information given him by Thompson, Clarkson was assured that his suspicions were correct, and that crews were obtained by lies and fraud.

Clarkson later gave Thompson credit in his journals for the help and support given to him “I perceived in a little time the advantage of having cultivated an acquaintance with Thompson of the Seven Stars. For nothing could now pass in Bristol relative to the seamen employed in this trade, but it was soon brought to me.”

“I was determined to inquire into the truth of the reports that seamen had an aversion to enter, and that they were inveigled, if not often forced, into this hateful employment. For this purpose I was introduced to a landlord of the name of Thompson who kept a public house called Seven Stars. He was a very intelligent man, well accustomed to receive sailors when discharged at the end of their voyages, and to board them till their vessels went out again, or to find them”